Asked by Mercedez Miller on May 14, 2024

Verified

In many (if not most) circumstances, cutting prices to increase sales volume is not a good idea. Explain why this is so. What are some alternatives that are preferable to cutting prices?

Price Cutting

A competitive strategy whereby a company lowers its product prices to attract customers and increase market share.

Sales Volume

The total number of units of a product sold within a specific time period.

- Comprehend the complexity and strategic thinking required in determining prices.

Verified Answer

JM

Jacob MarcanoMay 14, 2024

Final Answer :

All marketers understand the relationship between price and revenue. However, firms cannot charge high prices without good reason. In fact, virtually all firms face intense price competition from their rivals, which tends to hold prices down. In the face of this competition, it is natural for firms to see price cutting as a viable means of increasing sales. Price cutting can also move excess inventory and generate short-term cash flow. However, all price cuts affect the firm’s bottom line. When setting prices, many firms hold fast to these two general pricing myths:

Myth 1: When business is good, a price cut will capture greater market share.

Myth 2: When business is bad, a price cut will stimulate sales.

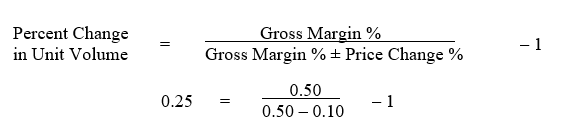

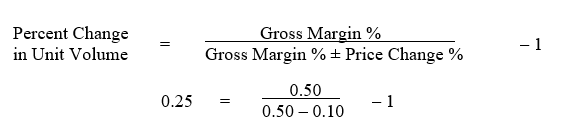

Unfortunately, the relationship between price and revenue challenges these assumptions and makes them a risky proposition for most firms. The reality is that any price cut must be offset by an increase in sales volume just to maintain the same level of revenue. Let’s look at an example. Assume that a consumer electronics manufacturer sells 1,000 high-end stereo receivers per month at $1,000 per system. The firm’s total cost is $500 per system, which leaves a gross margin of $500. When the sales of this high-end system decline, the firm decides to cut the price to increase sales. The firm’s strategy is to offer a $100 rebate to anyone who buys a system over the next three months. The rebate is consistent with a 10 percent price cut, but it is in reality a 20 percent reduction in gross margin (from $500 to $400). To compensate for the loss in gross margin, the firm must increase the volume of receivers sold. The question is by how much. We can find the answer using this formula:

As the calculation indicates, the firm would have to increase sales volume by 25 percent to 1,250 units sold in order to maintain the same level of total gross margin. How likely is it that a $100 rebate will increase sales volume by 25 percent? This question is critical to the success of the firm’s rebate strategy. In many instances, the needed increase in sales volume is too high. Consequently, the firm’s gross margin may actually be lower after the price cut.

Rather than blindly use price cutting to stimulate sales and revenue, it is often better for a firm to find ways to build value into the product and justify the current price, or even a higher price, rather than cutting the product’s price in search of higher sales volume. In the case of the stereo manufacturer, giving customers $100 worth of music or movies for each purchase is a much better option than a $100 rebate. The cost of giving customers these free add-ons is low because the marketer buys them in bulk quantities. This added expense is almost always less costly than a price cut. And the increase in value may allow the marketer to charge higher prices for the product bundle.

Myth 1: When business is good, a price cut will capture greater market share.

Myth 2: When business is bad, a price cut will stimulate sales.

Unfortunately, the relationship between price and revenue challenges these assumptions and makes them a risky proposition for most firms. The reality is that any price cut must be offset by an increase in sales volume just to maintain the same level of revenue. Let’s look at an example. Assume that a consumer electronics manufacturer sells 1,000 high-end stereo receivers per month at $1,000 per system. The firm’s total cost is $500 per system, which leaves a gross margin of $500. When the sales of this high-end system decline, the firm decides to cut the price to increase sales. The firm’s strategy is to offer a $100 rebate to anyone who buys a system over the next three months. The rebate is consistent with a 10 percent price cut, but it is in reality a 20 percent reduction in gross margin (from $500 to $400). To compensate for the loss in gross margin, the firm must increase the volume of receivers sold. The question is by how much. We can find the answer using this formula:

As the calculation indicates, the firm would have to increase sales volume by 25 percent to 1,250 units sold in order to maintain the same level of total gross margin. How likely is it that a $100 rebate will increase sales volume by 25 percent? This question is critical to the success of the firm’s rebate strategy. In many instances, the needed increase in sales volume is too high. Consequently, the firm’s gross margin may actually be lower after the price cut.

Rather than blindly use price cutting to stimulate sales and revenue, it is often better for a firm to find ways to build value into the product and justify the current price, or even a higher price, rather than cutting the product’s price in search of higher sales volume. In the case of the stereo manufacturer, giving customers $100 worth of music or movies for each purchase is a much better option than a $100 rebate. The cost of giving customers these free add-ons is low because the marketer buys them in bulk quantities. This added expense is almost always less costly than a price cut. And the increase in value may allow the marketer to charge higher prices for the product bundle.

Learning Objectives

- Comprehend the complexity and strategic thinking required in determining prices.

Related questions

Identify and Discuss Reasons Why Firms Become So Infatuated with ...

Mass Customization Attempts to Blend Unique Features into Standardized Goods ...

In What Pricing Strategy Customers Are Asked How Much They ...

A Grocery Store Offers Cans of Vegetables at 10 for ...

Sets the Price According to Demand ...